Probably the most unusual thing about Godzilla’s first film is that for several decades the majority of Western Godzilla fans had never seen it. The first film in question, of course, is Gojira, released in 1954 in Japan. What American audiences had seen instead was Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, a recut version of the film released in 1956 that added newly shot scenes of American actor Raymond Burr as roving international reporter Steve Martin, resulting in some key thematic differences.

Gojira is a surprisingly dark and serious film, considering it features a man in a rubber dinosaur suit stomping on model houses for a fair chunk of its running time. It was a direct response on the part of director Ishiro Honda and screenwriter Takeo Murata to not just the dawn of the nuclear age that announced itself in such a brutal and tragic form over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki nearly a decade earlier, but to the ongoing dangers of nuclear testing being done with no consideration for potential consequences. Early in 1954, a Japanese fishing boat called the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) was exposed to nuclear fallout from an American H-bomb test. It’s no coincidence that Gojira opens with a Japanese vessel suffering a similar fate at the hands of the titular radioactive lizard.

The very beginning of Gojira is a spare and stark credits sequence to music, punctuated repeatedly by Godzilla’s now world famous roar. The unique sound was created by running a resin-coated glove along the strings of a double bass and slowing it down. Future films would play around with the roar, giving Godzilla more character and even occasional pseudo-dialogue with it, but in its first appearance here it is an eerie, otherworldly sound. If you listen with the roar’s origin in mind, you can almost see the glove running along the strings of the instrument, but it remains a strange and singular piece of audio design.

A peaceful evening on the ship Eiko-maru comes to an abrupt end as a deafening noise and bright flash indicate a vicious attack from an unknown assailant. The parallel to an atomic blast is unmistakable here.

Also most fans’ reaction to the 1998 American Godzilla film.

Authorities send a local fishing boat to see what happened to the Eiko-maru, and that ship is also lost to Godzilla. In the subsequent scenes I was struck by the fact that Gojira instantly portrays the worry and fear of the sailors’ loved ones demanding answers. Within its first six minutes, Gojira shows more thought regarding the consequences of mass destruction than Zach Snyder’s Man of Steel (2013) shows through its entire running time.

“He didn’t even try to move the fight away from Metropolis. What the hell was that about?”

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of a fishing village on Odo Island are holding a beachside vigil for their missing fishermen. A raft of debris with an injured sailor is spotted, and the villagers pull it to shore to rescue their kinsman by violently shaking and slapping him, which is of course the recommended first aid for a person who has been starved, without water and exposed to the elements for several days on end.

(No, it isn’t.)

Reporters arrive to cover the story of the lost boats, but don’t get much help from the locals. The elder of the village tells them the story of Godzilla, an immense ocean monster whom the villagers had traditionally blamed for bad fishing. Human sacrifice was once a method by which they deterred Godzilla from coming ashore and devouring people, but now they perform ritual dances instead. Later that night, during a massive storm, Godzilla attacks Odo Island, crushing houses and injuring and possibly killing several people in the process. The survivors maintain the damage was done by a creature, not the storm; the same creature that sank the two ships. Much like Them! (1954), Gojira does not show its monster at first, preferring an effective buildup along the lines of a mystery story.

Dr. Kyohei Yamane, a prominent paleontologist, is put in charge of an expedition to investigate Odo Island and find out exactly what is going on. Many areas of the ruined village are found to be extremely radioactive, most notably a gigantic footprint made by an insanely large animal. Inside the footprint, Professor Yamane finds a trilobite, a creature that has been extinct since early prehistoric times.

In the ’50s, radiation couldn’t harm you as long as you wore a hat with your cleansuit.

Suddenly an alarm sounds, and word arrives that the monster has surfaced on the other side of the island. Everyone rushes to the top of the hill that overlooks the other side, only to be greeted by our first actual look at Godzilla, peering over the crest of that hill. Oddly enough, this first look at Godzilla is not of the standard suit but a handpuppet version that doesn’t really resemble the full-sized suit’s head all that well. It has prominent ears and mildly googly eyes, but the scene at least gives you an idea of Godzilla’s size, and features his first onscreen roar.

“I like mittens!”

Yamane gathers his daughter Emiko, clad in epic mom-waist slacks, and her boyfriend Ogata, and beelines back to Tokyo to report his findings. During the traditional “scientist with slideshow explains the science” ‘50s monster movie scene, Gojira makes some pretty massive factual stumbles. Yamane shows the assembled government types a slide of a tail-dragging sauropod, followed by a T-Rex, commenting that “About 2 million years ago, this brontosaurus and these other dinosaurs roamed the Earth during a period the experts called the Jurassic.” That’s a lot of wrong packed into once sentence, considering that:

- Dinosaurs went extinct approximately 65 million years ago.

- Brontosaurus was not a real species, but an apatosaurus skeleton with the wrong skull put on it (to be fair, few people outside of paleontology knew this in 1954).

- The Jurassic Period started around 200 million years ago and ended around 145 million years ago.

- The T-Rex shown in the second slide lived in the Cretaceous Period, after the Jurassic Period ended.

Yamane goes on to claim trilobites have been extinct for 2 million years, but they died off in the Permian mass extinction, 250 million years ago. And this guy is supposed to be a leader in his field. The 1956 U.S. version cites the same statistics and numbers, so it’s unlikely to be a translation error on the part of the modern subtitles. Oddly, the one major difference between the Japanese and English versions of this scene is Godzilla’s stated height. The Japanese version says Godzilla stands about 50 meters (164 feet) tall judging by the hill he’s towering over, while the U.S. version says he stands 400 feet tall. That is one tricky hill.

Japan’s Self Defense Force mobilizes in preparation for the possibility that Godzilla could surface in Tokyo Bay itself. Akira Ifukube’s dramatic score plays over footage of rolling vehicles and military activity, shot by Ishiro Honda during actual Japan SDF maneuvers. Ifukube would go on to score eleven more Godzilla films, and his musical themes are very closely identified with the character of Godzilla himself. Here in their original form, set to their original imagery, his score for the military scenes conveys strength and hope on the surface, while still containing a definite note of pessimism underneath. Ifukube makes the mobilization montages in the film feel like impressive but empty displays of power; ants building defenses against an oncoming bulldozer.

Emiko and a reporter go to see the reclusive Dr. Serizawa, Emiko’s old flame who threw himself into his work and out of their relationship after he lost an eye in the war. She believes his research may be able to help defeat Godzilla, but he flatly dismisses the idea and the reporter leaves. Once alone with Emiko, however, Serizawa confides that he has developed a new weapon, but refuses to allow it to become public knowledge. He unleashes the weapon in a fishtank while Emiko watches, but we are not shown what its exact effects are.

Aside from extreme overacting.

Dr. Serizawa, by the way, is played by Akihiko Harata, a famed Japanese character actor in his first of seven Godzilla movies. He’s also the only actor to appear in the debut films of the Toho kaiju holy trinity – Godzilla, Mothra, and Rodan. He specialized in scientists in the Godzilla series, and was to appear in the 1984 reboot Return of Godzilla but died of lung cancer before shooting began.

Akihiko Harata as Dr. Serizawa, all-around badass.

Like clockwork, Godzilla pops up in Tokyo Bay, totally ruining a boat party and wreaking havoc briefly before returning to the water. A plan is quickly hatched to build a 30 meter tall, 80 meter thick electric fence to electrocute Godzilla to death the next time he shows up. A lengthy building montage shows the building of this massive structure, interspersed with civilians fleeing to shelters. Many of the fleeing civilians are shown carrying furniture with them, which makes me wonder just how spacious these shelters are.

Faced with a 50-meter dinosaur attack, your first thought was “Save the cabinets!”

Meanwhile Yamane is distraught that everyone just wants to kill Godzilla rather than study him. In particular he wants to learn how an organism could absorb so much radiation and survive, which is a fair point outside of the whole “kills dozens if not thousands every time he shows up” thing. Yamane also does not expand on how one would go about studying a living Godzilla.

“Maybe a giant robot version of Godzilla could be used to subdue him…no, that’s just ridiculous.”

Godzilla surfaces once again and beelines for the giant electric fence, which is substantially less than 80 meters deep. In what will become a familiar sight in kaiju films, he rips through the defensive line like it’s not even there. All that montage work for nothing.

It wasn’t until the ’80s that montage technology would advance to the point that things built during them would always work later.

This scene also marks the first appearance of Godzilla’s radioactive fire breath, unfortunately portrayed by the goofy puppet spraying smoke out of its mouth. Godzilla’s ability to devastate areas and foes with fire breath is likely a reference to the enormously destructive firebombing of Tokyo and other Japanese cities in World War II. The cities’ structures, being primarily wooden, burned completely out of control, and during one strike on Tokyo it’s estimated that between 80,000 and 130,000 civilians died. Many elements of Godzilla’s design are meant to evoke aspects of war horrors suffered by Japanese civilians, something not often remembered today. For instance, the inspiration for the irregular bumps that cover Godzilla’s skin was the scarring on survivors of the A-bombs, suggesting that he’d been burned by the radiation he absorbed. Think about that when they show closeups of the puppet that looks like Cookie Monster’s reptilian cousin.

“C is for Civilian Casualties, that’s good enough for me.”

Godzilla rampages through Tokyo, and there’s simply nothing the military or anyone else can do to stop him. Despite this being the first use of what would be called “suitmation” in a film, the modelwork and scale is impressive and often surprisingly convincing. The level of detail put into the miniatures that would subsequently be stomped and smashed is astounding, all due to master special effects artist Eiji Tsubaraya, who would continually raise the bar in subsequent Toho kaiju films.

There are also a few composite shots that really work well, particularly one showing Godzilla looming over an apartment building while the silhouettes of people inside run around in panic. Of course, you have to wonder why they’re still in the building and not already evacuated, but I’m okay with a cool shot trumping logic now and again.

Technically I guess it’s pretty unlikely that he’d come to your specific building.

One shot that struck me as very interesting shows Godzilla passing behind a huge aviary. He stops for a moment and seems to eye the birds inside briefly before moving on. Thirty years later in Return of Godzilla, a connection would be drawn between the monster and birds, building on the emerging research at the time indicating that certain dinosaur species were likely ancestors of modern birds. This shot predates serious research into the idea that birds are descended from dinosaurs (the so-called “Dinosaur Renaissance”) by over a decade, so it’s an example of accidentally accurate future science in a movie that got the extinction of the dinosaurs wrong by 63 million years.

“This next fireblast is for all the saurischians out there!”

Gojira never lets us forget that the spectacle of Godzilla’s rampage has a human cost. People are continually, if indirectly, shown being crushed by collapsing buildings, falling from crumpled towers, and fleeing from fire they can’t possibly outrun. Long shots of the monster standing amidst the ruins of Tokyo must have been powerful imagery for the Japanese public, who had experienced the real thing less than ten years earlier. Indeed, many countries around the world likely found these scenes disturbingly familiar. Gojira drives it all home with a scene of a mother and her children, huddled in Godzilla’s path with no chance of escape. The mother reassures the children that “We’ll be joining your father soon.” The kids are young, but maybe not too young for their father to have died in the war, or possibly in the turmoil following the war. It’s a haunting image.

12 years later, Godzilla would do a jumping victory joy dance after beating the crap out of a giant lobster.

Godzilla wades back out into the bay, and jet fighters show up to unload missiles at him. The jets have an astounding amount of trouble hitting a 150+ foot tall lizard, and do incredibly dangerous flybys after unloading their armament. Air forces not understanding that you don’t have to fly within arm’s reach of your target after shooting it is a proud monster movie tradition that dates back to at least King Kong (1933). Surprisingly, the jets do the trick, and Godzilla retreats beneath the waves.

“I’m just going to head out now, because you guys are even embarrassing me at this point.”

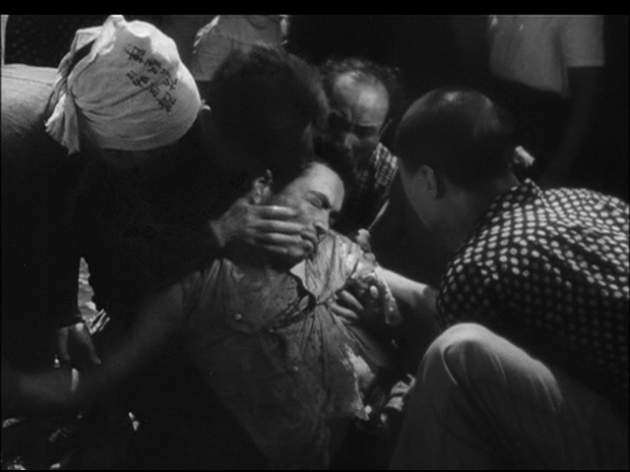

The attack is followed by scenes of triage and despair, as Tokyo attempts to assess the damage and treat the injured. A young boy is scanned with a Geiger counter by a doctor who shakes his head sadly. A daughter wails as her wounded mother is taken away. Emiko is in the thick of all this, and decides she can’t keep Serizawa’s secret if it could possibly spare the world from another attack by Godzilla. She and Ogata go to plead with Serizawa to use his weapon to try and stop the monster.

Serizawa reveals that his invention is called the Oxygen Destroyer. He explains that, “Overall, it’s a device that splits oxygen atoms into fluids,” which is the chemical equivalent of saying the dinosaurs died out 2 million years ago. The point is, it destroys all the oxygen in an area of water, and that makes it a potent weapon. Serizawa believes he can refine it into something beneficial, but is too concerned about it being misused to reveal it to anyone. However, television images of death and destruction, like nothing that would be seen again in the Showa Series, change his mind. Serizawa destroys his research, and agrees to use the Oxygen Destroyer against Godzilla.

Having pinpointed the area Godzilla is most likely resting in, a ship carrying all the main characters, a bunch of reporters, and a naval crew prepares to unleash what may be humanity’s last hope. Surprisingly, the press seem to know exactly what the Oxygen Destroyer is and basically what it does. You’d think you could just say “We’re going to use an advanced depth charge” and leave it at that, as opposed to spelling out exactly what the horrifying superweapon is.

Serizawa insists on going down to activate the device, over the protests of Ogata, who accompanies him. They find Godzilla resting on the bottom. Motioning Ogata to return to the surface, Serizawa unleashes the Oxygen Destroyer, and cuts his air hose and lifeline so the secret of the weapon will die along with him.

Even in a ridiculous old-fashioned diving helmet – total badass.

Godzilla thrashes about, rises to the surface in agony, and sinks back down as the people on the ship watch in horror. The Oxygen Destroyer reduces him to a skeleton that comes to rest on the bottom, and then disappears. There is very little triumph in the end. Serizawa’s sacrifice is greatly mourned, and the killing of Godzilla is not celebrated. The death of the monster was a necessity, but no one takes joy in it. As the gathered crowd pays homage to Serizawa, Professor Yamane warns that more ancient and unknown beasts are probably out there, and continued nuclear testing will likely result in more Godzilla-like creatures.

Stuffed Godzillas are available in the lobby, kids!

Compare this message of warning with the U.S. ending, which features Raymond Burr opining in narration that a great man was lost, but “the world could wake up and live again!” Like most American fans, I grew up exclusively exposed to the Godzilla, King of the Monsters! version of the movie. The Japanese film did play in the ‘50s and ‘60s in predominantly Japanese neighborhoods, and the uncut and subtitled Gojira made the film festival rounds starting in the early ‘80s. In 2004, Gojira was finally released on DVD in Region 1, and a subsequent Criterion Collection release has restored the film to near pristine image quality. The difference between the original and what I had seen so many times as a kid was striking.

While it’s hardly an upper of a film, the U.S. version has carefully excised most of the social commentary related to nuclear testing and certainly takes pains to not suggest that nuclear weapons were ever used on Japanese soil, because why would that come up in such a situation? Instead, Godzilla is presented as almost a natural disaster, or a freak occurrence that could potentially happen anywhere in the world. The scenes of destruction are no less reminiscent of the horrors of war so recently visited upon Japan, but Gojira is very frank about the connection between the monster and the past, whereas Godzilla, King of the Monsters! dances around it using Steve Martin’s point of view as a filter.

Gojira received mixed reviews at best when it premiered in Japan, and many critics thought it was simply too soon after the events that inspired it. The film resonated with audiences, though, and it was nominated for Best Film and Best Special Effects by the Japanese Movie Association that year. It won the latter award, but lost Best Film to Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, which should give you an idea of how much ass Japanese cinema was kicking in 1954.

Watching it today, Gojira has a stark and oddly haunting quality to it. All too often the image that Godzilla conjures up is one of goofy monster battles and space aliens with wacky world domination plots. This first film has real soul behind it that is obvious even 60 years later. Under all the tumbling model cars and googly puppet eyes, director Honda was trying to find a way to exorcise some very scary demons, ones that should be recognizable to anyone living in a nuclear-capable world.

Buy Gojira on Amazon